It's going to get cold -- let's review ice safety!

Take the 2025 polls; some photos from Greenwich, Cossayuna

First, take this quick poll. It’s anonymous.

At Least the Weather Is OK … for Now…

Spring might be in the air here in Clarks Mills to start the year. Want proof? See this little 9-second video.

That’s the FedEx guy who was late in delivering a very important Christmas present, but we digress.

Here are some stills from yesterday…

But all of this is just a mirage. It’s about to get bitter cold again, so now is a good time to review ice safety with our Outdoors Tomorrow columnist Bob Henke…

Know ice safety before you go out

By Bob Henke

Journal & Press

During my first winter as a Conservation Officer, I found myself hurtling along the frozen surface of Lake George on a snowmobile, trying to keep up with my more seasoned partner who was leading on a more powerful sled. “Hurtling” is a relative term. In those days, a 60 MPH snowmobile was a rocket, and the ones the state purchased were lucky to hit 35. However, it predated snowmobile suits, helmets, heated hand grips and suspensions so it was quite a ride, particularly in below zero weather. The other officer was Tom Callahan, riding a big orange Massy-Harris snowmobile. I was on a bottom-of-the-line Ski-Doo, which did not even have a brake–you had to pay extra for that as well as for a windshield, which it also lacked. Our radios were the lunch-box portables that took 12 D-cell batteries and had an effective range measured in yards although they could be used to heat up hot dogs speared on the antenna or set your jacket on fire if it was against you while transmitting. Speaking of setting your jacket on fire, the reason that I had that machine was because Conservation Officer Ron Robert decided to buy his own to use–one with a windshield. Seems he was roaring down Brant Lake on the Ski-doo, with his ubiquitous corn cob pipe clenched in his teeth. The wind coming over the top of cowling stoked it like a forge, causing the glowing pipe to burn right through the bottom, showering Ron’s jacket with sparks and setting him quite on fire. He wound up in his red union suit trying to load the sled back on the trailer and get home for more clothes.

But back to the original story. As we crossed a small bay, I was horrified as the ice shattered as my partner’s sled passed. Ten feet behind him, and following along for about 30 yards, the ice exploded, going from solid trail to platter-sized ice floes floating over 40 feet of black water. Stopping was not an option because, remember, brakes were too, and the state did not pay for “frills.” My only choice was full throttle and try to skip over the abyss. Unbelievably, this worked, and I made the shore, plunging into about three feet of fluffy snow, where I sat gibbering and thanking my genes for good bladder control. My partner did not miss me for 15 minutes. When he finally called on the radio, I told him what happened and a half hour later he arrived, coming along the shore, not on the ice. It was then I learned the proper procedure when your sled got wet was to turn it on its side and race the engine, spinning the track to dry it. Otherwise the bogey wheels might freeze solid– which they had. After three hours by a roaring fire, the sled was operable, and I was thoroughly lectured. We were back to the cars well before midnight, having bushwhacked along the shore the whole way. Callahan contended it was entirely my fault for not “reading the ice.”

I recall my grandfather waxing eloquent about “reading the ice.”

There is folk wisdom about ice safety. Gramp said, “two inches will hold a man, four inches will hold a team, and 5 inches will hold a wagon.” Then he qualified it with elaborate explanations about blue ice, black ice, fluff ice, honeycomb ice, new ice, old ice, slob ice and a few other descriptors calculated to boggle a 10-year-old.

It worked.

It was not until college physics, where I learned how water freezes, that it became clear. Ever notice how lakes seem to freeze over suddenly? One night there is open water and the next morning it is solid ice. It works like this. The surface water is cooled by the cold air. This makes it denser than the water underneath and the cold-water sinks. The downward movement of cold water takes place all around the edges of the lake and forces warmer water up in the center of the lake where it in turn is cooled. This starts a circular movement, up in the center, down around the edges, which continues until the entire mass of water is cooled to about 45 degrees. Now there is not enough temperature difference to move the water, ice forms across the entire surface of the lake in a few hours of cold and people start wanting to walk on it. The first keys to evaluating ice safety are visual. When water first freezes, “new” or “black” ice is clear and brittle. It rests directly on top of a very dense, cold layer of water. It is transparent, you see the water beneath and the ice appears dark. Black ice may get up to two inches thick but is very treacherous! Its brittleness makes it sensitive to vibration so the rhythm of walking or, as I learned so well, a motor can cause an area up to several hundred square feet to suddenly shatter into palm-sized pieces. It is a crystal, like glass, so ice itself is not strong. It supports weight because it floats. Like a boat, it can hold only so much weight. If it snows on black ice, the weight forces the ice downward, opening cracks, and allowing water to seep to the surface where the snow soaks it up like a giant sponge. This freezes on top of the black ice and is milky white. White or “fluff” ice is filled with air bubbles and is dangerous. It is like walking on a floating block of Styrofoam. It supports a lot unless there is a crack, whereupon it flips up, dumps you in, and closes back over the top. Snow cover or a layer of white ice insulates and slows the freezing process, but clear cold nights will finally “make ice,” freezing from the bottom in successive interconnected layers. The best ice is that which builds up these interlocking layers of crystals. You may have noticed this as both vertical and horizontal lines in sides of ice fishing holes. The strong interlaced structure makes it opaque and gives the ice a blue or flat grey color. Four inches of “blue ice” is usually considered safe for most winter activities—but I like a foot or more. Blue ice also reflects most of the indirect winter sun, accounting for that sunburned face after a day of ice fishing.

In the spring, increasingly direct rays of the sunshine through the ice, warming the underlying layer of water and restarting the circular movement in reverse. This movement, coupled with warm water from spring run-off, melts certain areas faster than others. In a smooth bottomed lake, melting takes place first along the edges. Now we can have a very inconsistent cover known as “honeycomb” ice. The pockets of much thinner ice look dark, giving the surface a spotted appearance. This is the ice that holds you just fine in one place and drops you through a few feet away.

Falling through the ice is never fun. I wound up with only psychological scars; you may not be so lucky. The fact that someone went ahead of you is no assurance that you can also proceed safely, especially during a winter with fluctuating temperatures. Reading the ice is a valuable skill but far better is checking the ice as you go. Back in the Conservation Officer days, I made a “Game Warden Staff” for each of my officers. The point was sharpened and, after a little practice getting the force right, a sharp poke would thrust it through any ice less than two inches thick. The back of the hook was flattened to catch against the ice and allow you to push up and slowly back off the thin ice. The hook itself was designed to probe under the ice on a beaver trap site so the chain with the trapper’s name could be withdrawn and checked without exposing a hand to the anchored trap below the ice. The end of the hook was sharpened so if the worst happened, it could be driven into the ice to pull yourself out of the water. The handle was intentionally long so it was buoyant enough to float the staff if you lost your grip at any time in the fracas.

There are also commercial products available. The Bohning Company, an archery and sporting equipment manufacturer, makes an ice safety device called the ADK 3-in-1 Spud. This has a special stepped chisel head to quickly cut through ice and a built-in scale to measure the ice thickness. It comes apart to produce a very secure anchor to hold a rope used in rescue operations if someone goes through. In less than a minute, the tool can be used to make a hole in the ice, set an anchor, and get a rope to someone who has fallen through the ice. Every second is precious in these conditions.

If you go through in a vehicle, it is critical to get away from that machine as rapidly as possible. Research has shown that in water depths above about eight feet, every type of vehicle somersaults and sinks upside down. If an article of clothing is hooked on a sled or ATV, you can be anchored to it and, in a vehicle, it often buries itself in the bottom muck so deep you cannot get out of a window.

For any trip on the ice, you should have some minimum equipment. There are specially designed float coats made specifically for ice sports. These keep you warm as well as buoyant during a plunge. If you are not carrying a staff, a pair of ice spikes on a lanyard around your neck, will be crucial to saving yourself if you are alone. No one should go on or around the ice without a 100-foot length of floating rope. The thicker the better—a minimum of half inch. It is difficult to grip thinner lines during emergency situations. Once again, there are commercial alternatives, ropes inside a “throw bag” that make it easy to accurately toss the line long distances and provide a thick gripping point for the victim. In the game warden days, we coiled it inside plastic half-gallon jugs with the back cut out to achieve the same result.

Finally, the victim must assist in their own rescue. The tendency, whether saving yourself or being saved, is to bend over the ice edge with your legs pointing downward. This makes a very effective “hook” so it is impossible to pull you out. If being pulled out, the best approach is to come out of the hole either on your back or side instead of frontwards. If you are pulling yourself out either with spikes or simply flailing out, strongly arch your back backwards and kick as hard as possible to essentially swim out of the hole.

The best solution, however, is to be careful and be aware so as not to fall through in the first place.

Contact Bob Henke with your sightings or questions by mail c/o The Greenwich Journal & Salem Press, by email at outdoors.tomorrow@gmail.com.

And Now for the Comics — ‘Filbert’ by LA Bonte

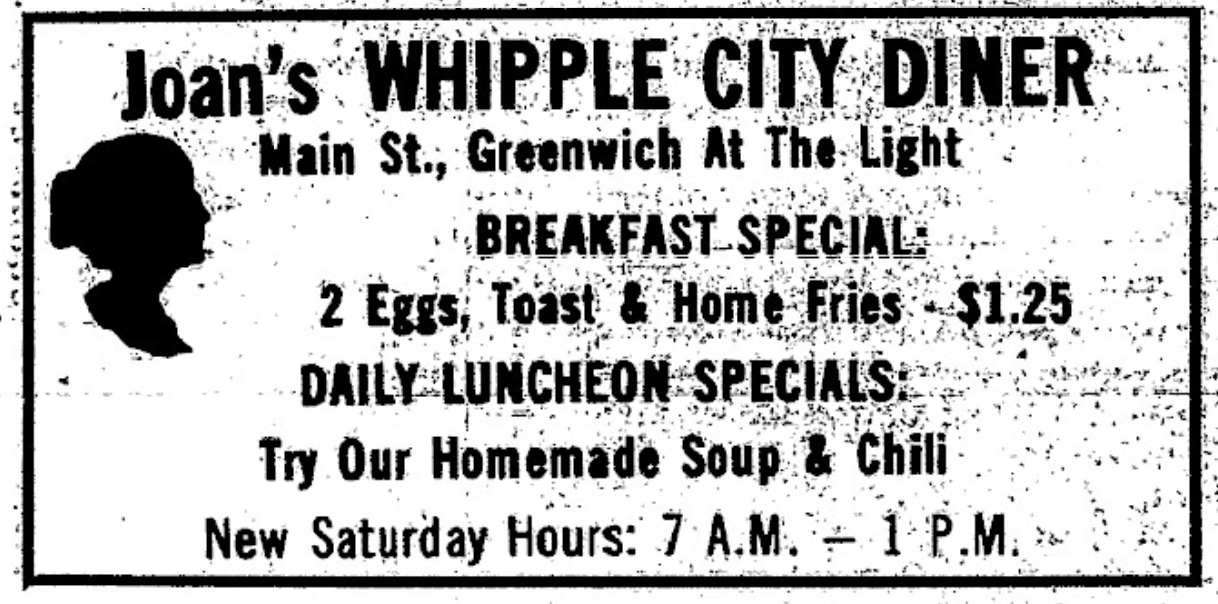

An Ad From 40 Years Ago in the Journal & Press:

Now that’s a price we can believe in!

More tomorrow!

I remember skating on a neighbor’s pond with my mom, my daughter and son, and our dog years ago. It was black ice, probably just under 2 inches thick, crystal clear, and beautiful, as was the water underneath. You could see everything down to the bottom, even see some little creatures still moving around. It was magical, like skating on the water itself. We had no idea it could be dangerous! A beautiful memory, but I am glad it didn’t end in a three generation tragedy!