Print Update: Just a quick note on print subscriptions — we’re working on a new issue to hit by Saturday, and we still have the old rate available (haven’t changed the price on the web site yet). So if you’d like to add a year to your current subscription, or start a new one, you still can for only $42/year! Offer will end this weekend!

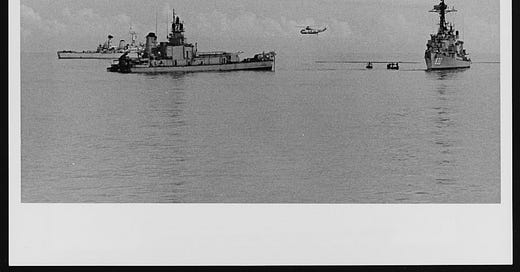

The sad end of the USS Evans

By Lance Allen Wang

Journal & Press

It was just after three in the morning, June 3, 1969, in the South China Sea. The United States Navy destroyer USS Frank E. Evans’ captain, Commander Albert McLemore, had gone to his cabin just past midnight after, by all accounts, having gone about 36 hours without sleep. Manning the bridge of USS Evans that night were two young junior grade Lieutenants who had taken over around midnight. The Officer of the Deck was Lieutenant Ronald G. Ramsey, and the Junior Officer of the Deck was Lieutenant James A. Hopson. Evans was participating in a SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization) Naval exercise, SEA SPIRIT, prior to its return to Vietnam from Subic Bay Naval Station in the Philippines. During this portion of the exercise, Evans was one of four ships (three American destroyers and one British) providing an escort for HMAS Melbourne, an Australian light aircraft carrier.

To prepare for an anti-submarine patrol, the Australians prepared to launch an observation aircraft from their deck. Because there had already been a couple of near collisions with the carrier during this exercise, HMAS Melbourne had all its navigation lights on full brightness. They ordered USS Evans to maneuver to a position near the carrier called “plane guard,” where they could assist in rescue should the aircraft have a mishap during launch. Evans had already done it three times without incident. By all accounts, this was a routine maneuver in a routine exercise. What could go wrong?

Quite a bit. Inexperience on Evans’ bridge meant no one woke up the ship’s captain to advise of the new mission. It also meant that on Evans’ bridge, key information regarding change of course heading was getting confused between the Officer of the Deck and the Junior Officer of the Deck. Trouble was compounded because the carrier and its escorts were executing zig-zag maneuvers this entire time to protect against a notional submarine threat. It all added up to HMAS Melbourne and USS Evans having differing ideas what the other was doing – making what happened at 3:15 in the morning inevitable. With the sickening sound of tortured metal buckling and rending, HMAS Melbourne’s bow sliced through Evans just behind the bridge.

An Unlucky Ship

Sailors are a superstitious lot, seemingly at odds with the navigational science which ushered in an era of exploration and discovery some 600 years ago. But those who serve under great risk and with more than a hint of the unknown develop superstitions to make sense of the seemingly random intrusion of bad luck. Ask any soldier or Marine who served in Iraq about the Charms candy in the Meals Ready-to-Eat – they were finally removed from circulation in 2007. “I always throw mine away,” said one sergeant serving in Operation Iraqi Freedom, “Every time I eat the wrong color something bad happens.” Even this was a holdover from World War II through Vietnam, when canned apricots in the C-rations were accused of a similar form of deviltry.

With this said, it would stand to reason that a ship which has had a mishap would be considered unlucky. USS Evans was not an unlucky ship. She had a very distinguished record – she entered service during the last months of World War II, was awarded five battle stars during the Korean War, and had already supported operations in Vietnam. Throughout all this period, she served honorably, and among her nicknames was yes, “Lucky Evans.” If there was a ship involved in the exercise that could be considered unlucky, it was HMAS Melbourne.

Five Years Prior

In February 1964, HMAS Melbourne experienced a tragic foreshadowing of the Evans collision. While undergoing sea trials in Australia’s Jervis Bay, another Australian Navy destroyer, HMAS Voyager was maneuvering to the plane guard position. While maneuvering on a defensive zig-zag course, the Voyager turned too early. The die was cast – while the aircraft carrier’s alarms sounded for 40 seconds, they only provided a sad soundtrack, as there was no way to avoid the collision at that point. Melbourne’s bow sliced cleanly through Voyager just behind the bridge. The Voyager’s senior officers on the bridge were killed, and the cruiser’s heavy bow sank, taking 82 of the 314 Australian sailors aboard to the bottom. The back half of the ship remained afloat for another three hours, allowing time for rescue and recovery operations.

Back to 1969

During the June 1969 SEATO exercises, there had already been a near miss for HMAS Melbourne. On the first night of the exercise, Captain John Phillip Stevenson of HMAS Melbourne met with the four captains of the destroyers providing his carrier’s escort, discussed the 1964 Voyager accident, and emphasized the need for caution maneuvering around the carrier. Despite this, at one point US Navy destroyer USS Everett F. Larson was assuming plane guard position, and only rapid response by both ships prevented a collision between Melbourne and Larson. This cast a more immediate shadow over the exercise, HMAS Melbourne, and her escort destroyers.

Rescue

As HMAS Melbourne sliced through the Evans at a speed of 18 knots, the sound was described as “… ear- splitting: 40,000 tons of Melbourne crashing into 2,200 tons of Frank E. Evans sounded like 50 automobile accidents happening at once,” by one of the American officers.

The destroyer’s bridge was torn open, dumping the occupants into the South China Sea. Lieutenant Hopson recalled seeing Melbourne overrun them: “I turned and saw a flash of light on the bridge… I was hit very solidly in the back and I was in the water.”

In the back half of the American destroyer, all were aware something very wrong had happened, but as sailors ran forward to see, they realized that most of the bridge and the bow of the ship were no longer there.

In the rear of the ship, the watertight doors were sealed during the exercise, therefore it was still able to float, though the ship was heavily damaged. However, for the front of the ship especially the darkened berths below deck, the closed watertight doors only presented one more obstacle to escaping.

Evans’ bow was still afloat but severely damaged and taking on water. With difficulty, a handful of sailors made it out during these few minutes. Commander McLemore, jarred awake by the collision in his cabin, soon found himself in the water, disoriented, after struggling out of the wreckage.

As the far less damaged Melbourne began coordinating rescue operations, the Evans’ bow sank beneath the waters, taking 78 sailors with her.

Once HMAS Melbourne realized that the back half of the Evans was going to stay afloat, its crew lashed the Evans to the carrier to allow the continued recovery of personnel and equipment from the stricken ship. There were numerous accounts of heroism by both Americans and Australians in the recovery of nearly 100 crew members of the Evans from the water.

The final toll was 74 killed. Only one body was recovered – all 73 entombed within Evans’ bow section remain forever deep below the South China Sea. The destroyer USS Evans was a total loss. HMAS Melbourne was sidelined five months for repairs.

Consequences

Following a joint investigation with the Australian Navy, the United States Navy ended up court-martialing three officers for the accident – Commander McLemore and Lieutenants Ramsey and Hopson, the Officer of the Deck and Junior Officer of the Deck on the USS Evans’ bridge at the time of the accident. The Lieutenants were both found guilty of endangering the ship through their actions and inactions. Commander McLemore was found guilty under his command responsibility for ensuring adequate leadership on the ship’s bridge. In a fundamental principle of military leadership, a ship’s captain delegates authority for subordinates to do their job on the ship - but always owns the responsibility. It is a concept that President Harry S. Truman civilianized with his descriptor of the Resolute desk - “The buck stops here.”

But was HMAS Melbourne “unlucky”? The way the odds were stacked against her, luck was the least of her problems on the early morning of June 3, 1969. Most of her problems were on the bridge of USS Evans. For 74 American sailors who died in the South China Sea and their stricken fighting ship, the question was sadly moot.

Lance Allen Wang is an Iraq Veteran and retired Army Infantry officer who lives in Eagle Bridge, NY, with his wife Hatti.

And Now for the Comics … ‘Animal Crackers’ by Mike Osbun

More tomorrow!