By Lance Allen Wang

Journal & Press

As America hurtles headlong towards the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, we are quietly passing several anniversaries of events which led up to July 4, 1776. We quietly passed the anniversary of the battles at Lexington and Concord, early military actions which served notice to the British that the colonies were going to capitulate neither quietly nor easily.

As we look back at the early years of the American Revolution, we see names which will echo through time, including that of our most famous and heralded commander, General George Washington. Washington is an iconic figure, and one who I’ve found who not only lives up to his legend is even more impressive in fact. But as both legend and events would grow Washington in stature, they equally shrank some who stood alongside him.

Some who stood alongside Washington would attain their own levels of fame – former bookseller turned general Henry Knox; French idealist Maquis de Lafayette; mountain warrior Daniel Morgan; the “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion. Others like Benedict Arnold would wear infamy. But some would find themselves simply lost to history. One of them arguably had the distinction of being the first commander of American forces – General Artemas Ward. Next month will mark the 250th anniversary of his handing over command of the Continental Army to Washington in July 1775.

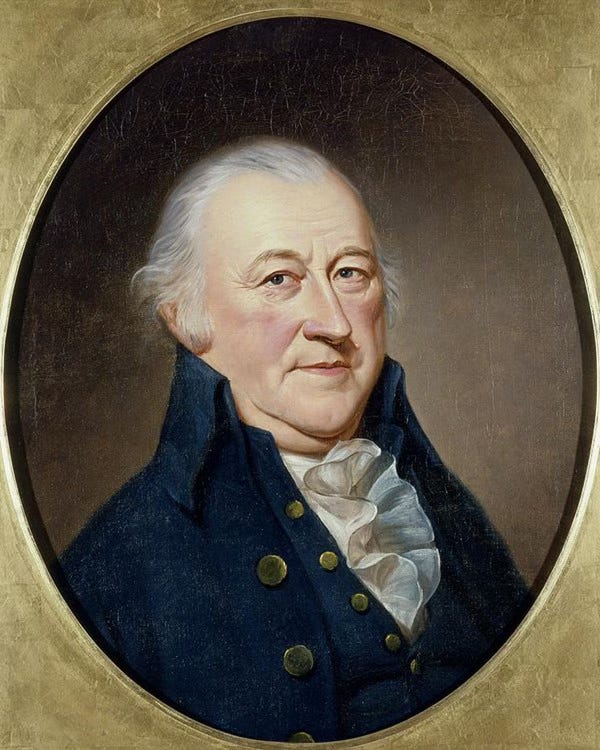

Like Washington, Ward was a gentleman farmer, though Ward tended his crops in the Massachusetts colony. Unlike Washington, he was neither tall nor distinguished looking, being described most often as “round and dumpy.” However, the leading citizen of Shrewsbury, Massachusetts was a Harvard graduate, a public servant in local and colonial government and like Washington, he was a military veteran having served between 1755-1757, leaving the service as a Regimental Colonel of the 3rd Regiment, Middlesex and Worcester County militia. He then returned to private life, where he continued involvement with local and colonial government.

His outspokenness would eventually cost him his military commission, the English government finding that his protestations about taxation, as well as his association with men like Samuel Adams and John Hancock, made his loyalty suspect.

By the early 1770s, as the independence movement gained strength, Ward remained an important figure. In October 1774, his old militia unit, the 3rd Regiment, resigned en masse from British service and joined the independence movement, electing Ward to lead them. Not long after, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety named Ward the commander-in-chief of all Massachusetts forces.

Following the battles at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Ward, knowing that the ad-hoc nature of the militia of the various states which were assembling about him would not suffice for an extended “shooting war,” established a camp for the Army near Cambridge, Massachusetts. Here he presciently began organizing the basis for a larger Army. He established recruiting, rules of conduct, focused on often overlooked details like logistics, and organized raids on the British forces which were now bottled up in Boston.

Congress commissioned George Washington as the commander of the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, appointing Ward as the senior Major General, second in command to Washington. As one commentary described it, in picking Washington to command, the Continental Congress was “gambling that his robust military record and stature as a Virginian would help unite the colonies.” Ward turned over command of the assembled forces to Washington in July when the new commander arrived. Ward would remain in the Boston area through the evacuation of the British, which took place in March 1776.

Not long after the British withdrew from Boston, General Ward applied to Washington to leave the Army due to ill health, telling his Commander, “I am now to inform your Excellency that I am in such an ill State of Health that I do not think myself capable of doing the duty which to be done by me… I must beg leave to resign my Command & to withdraw from the Army after the expiration of this month.”

As Washington was preparing to lead his Army south to confront the British in New York City, he could not afford to leave the Boston area bereft of leadership. He denied the request. Washington was able to convince Ward to command the Eastern Department for a while longer, and there Ward remained until 1777, when he returned to Shrewsbury. He would remain involved with politics, even serving in the United States House of Representatives for two terms during the 1790s.

Legacy

Major General Ward died, largely forgotten at the national level, in 1800. He had not gained much in the way of a military reputation, and he was even slandered in his time by his peers. He was not considered aggressive, had puritanical personal values yet was often lax in enforcing soldier discipline, and was notably disliked by Major General Charles Lee, who, as a former British officer prior to his joining the Continental Army, abhorred receiving orders from someone he saw as a mere bureaucrat. A biographer noted that Ward also held a grudge against George Washington, who he felt “Made remarks injurious to [his] Reputation” in 1775. While time has lost these unrevealed remarks, Ward never did. With Ward out of uniform by 1777 and his military reputation relatively undistinguished, it would end up falling to his descendants to unearth and rescue his reputation.

The Ward family’s deep ties with their hometown of Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, which helped prompt a resurgence in research and interest in the General. The first monument to him was raised in his hometown’s cemetery in 1847 at the insistence of his grandson Andrew Henshaw Ward. Later descendants would commission a biography in 1921, and would work with Harvard, his alma mater, to commission a statue of him in Washington, DC, dedicated at Ward Circle in November 1938.

Although seen as a less than martially commanding bureaucrat, credit must be given to Major General Artemas Ward for assembling and organizing the various and sundry raw militia forces which would become George Washington’s command. Unlike purely political generals might have done, he did not unwisely squander his forces after Bunker Hill – he stood fast and blockaded the British. He did not overestimate the capabilities of his forces despite recent victories. Ward’s prudence and organizational skills put him in a position to have forces to turn over to General Washington when he arrived in July 1775.

Postscript

One of America’s most popular humorists of the mid-19th century, Charles Farrar Browne, took an odd name out of history and called one of his characters “Artemus Ward,” differentiating himself from the General of old by one letter in his first name. In his stand-up act, Browne would invoke Artemus. Among one of his appreciative audiences was Abraham Lincoln, himself one to spin an amusing yarn in his time.

When talk began of dedicating a statue and traffic circle to Artemas Ward in Washington, DC 75 years later, several letters to the Washington Post expressed wonderment that the circle was being dedicated to a comic from the mid-19th century. If anything, this says far more about the place that General Ward found himself in history than it does the public’s ignorance of it. Much like the story of Peyton Randolph, the first President of the first Continental Congress (1774-1775), some history is always going to be consigned to the footnotes. Which at the very least also ensures that I’ll always have something to write about.

Lance Allen Wang is an Iraq Veteran and retired Army Infantry officer who lives in Eagle Bridge, NY, with his wife Hatti.

What a great story!!